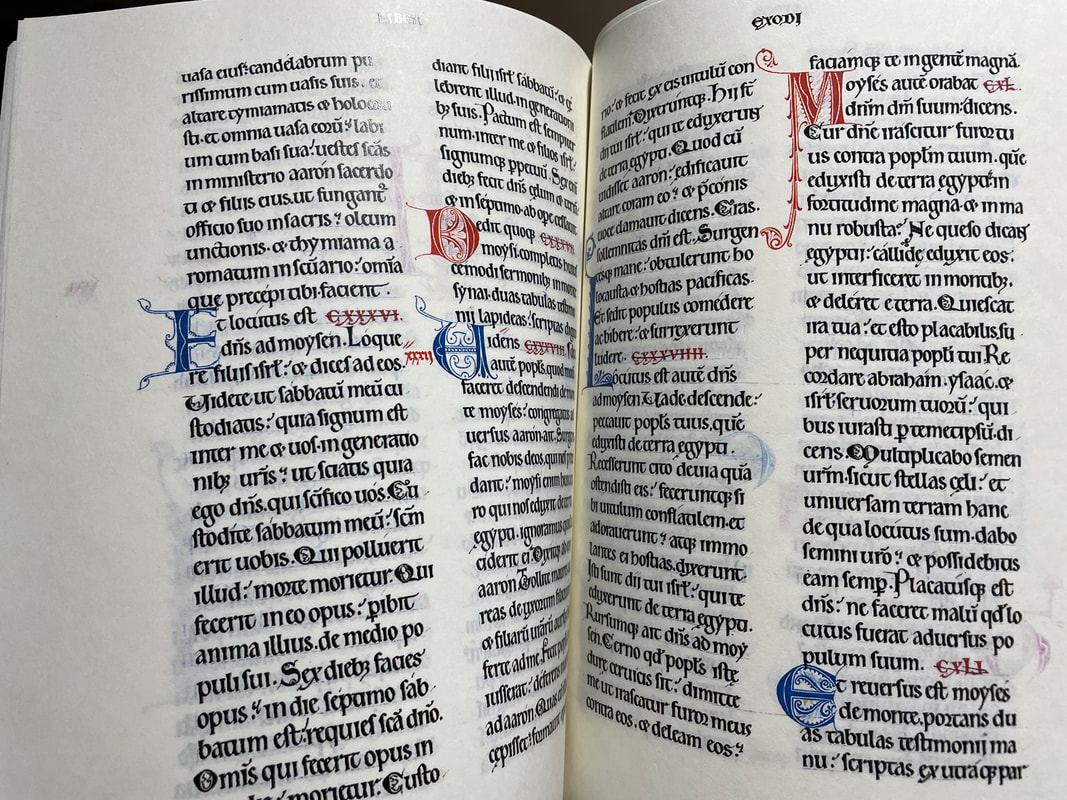

Produced c. 1160 - 1180 at the Abbey in Clairvaux between the Second and Third Crusades. (Pictured is a Facsimile of the Bible of Bernard of Clairvaux we are currently developing).

Produced c. 1160 - 1180 at the Abbey in Clairvaux between the Second and Third Crusades. (Pictured is a Facsimile of the Bible of Bernard of Clairvaux we are currently developing).

REASONS

Q: What got you started with old Bibles?

I handled an old Psalter, a manuscript of the Psalms, in the Rare Book Room of the Library of Congress in the early 1990s. Everything from its beauty, intense colors, and proportions of text to page size made an impact on me. I also saw the Gutenberg Bible, the first book printed on moveable type, on display and was overcome by its beauty. These old Bible are beautiful and part of the richness of Western culture. I vowed to myself that I would one day replicate them and also make them available for others.

I also noticed in my own collection of Bibles that many publishers were guilty of historical revisionism and misrepresentation. Did these publishers change the Bible? Yes. They removed books that had been in the Bible for over 1,000 years. A good example is the King James Version of 1611. When originally published, it contained the entire Apocrypha along with third and fourth Esdras. Then, all of these intertestamental books just disappeared. It was an editorial judgment to appease an offended market segment. Publishers reissued an abridged edition of that translation and claimed - even when in facsimile form - that they were offering the 1611 edition of the Bible. They even omitted the Translator’s Note to the Reader. They weren’t offering the 1611 edition of the Bible.

When I researched the contents of the Gutenberg Bible, the most famous of all Bibles, I was astonished to learn that this was a medieval Bible. It had more books. It had ancient prologues. And, the translation - the Latin Vulgate - had served Christendom for over 1,000 years. So, one finding after another lead me deeper and deeper.

FORMATS

Q: Will you make smaller sized Bibles?

Yes. We will offer at least two different 36 line Bibles in a letter sized, or 8 1/2” x 11” format. One will be based on the Bible of Bernard of Clairvaux, a non illuminated Bible in the French Romanesque Style (as pictured above). The other will be the “baby” Gutenberg, the 36 line Bamberg Bible also in a smaller sized format for personal use, and hopefully completed in 2021.

Q: Will you make your Reproduction Bibles available for a tablet reader?

No. The medium is the message. Tablets are nice. And, while online tools in a digital environment are certainly helpful in drilling down within the Scriptures, our mission is to produce tangible, tactile books intended to be handled and read within a social context. The question is akin to asking if we will ever outsource and have our Reproduction Bibles printed in China on newspaper quality paper in a pocket sized format. Such a question would never be asked after having seen a manuscript Bible from the medieval period or a Gutenberg Bible on display in a museum. Again, the medium is the message.

TRANSLATIONS

Q: Why are you using older translations?

We are using older translations partly because they are in the public domain and partly because they have stood the test of time. A translation, or work, that is in the public domain means that there is no copyright. While the text is copyright free, our work is copyrighted because of the extensive amount of art. Moreover, and perhaps more importantly, older translations are more literal in their rendering from the source language into the receptor language.

There is a balancing act when considering any translation. And that balance rests between a literal and dynamic equivalence rendering. The facts are these: some words poorly translate when taken from the original into English. Sometimes, there are no equivalents to convey an idea. In other words, sometimes an idea can get lost in translation. And sometimes, an idea for idea rendering can undermine the original intent of the original words.

Q: Why don’t you use modern translations?

Many modern translations are based on manuscripts, which were not available to translators from an earlier era. There is nothing wrong with that - even when there are variants - so long as key doctrines are not tampered with. The problem with modern translations, however, appear when key ideas get too confused or when the text of the Bible is forced to conform to a secular society that is politically correct and even hostile to the key teachings within the Bible. For example, Christ is not described as “the chief cornerstone,” but instead referred to as “the capstone” in some modern translations. Clearly, there is a problem with that. The bright morning star. What is it? Lucifer or Jesus? It cannot be both, unless you are an occultist, which we hold that the Bible refutes. Hence, there are some serious issues with some translations. Is it fair to impose an interpretation onto a word rather than render the word in translation? Consider the Latin word Lucifer. It appears in the Latin Vulgate, and it is an interpretation imposed onto the text. And, it is continued in some English translations. While that reading portion in Isaiah chapter 14 may be familiar and even theologically accurate, it is not an accurate translation and it undermines the metaphor intended by Isaiah. That word represents a doctrinal interpretation as well as a theology not found in the plain reading of the original in Hebrew or the first translation into Greek. In the Greek Septuagint, in contrast, the word is Hesperus, that is, Venus, both the planet and the god of mythology. In the ancient world, Venus was also known as Ishtar. Hence, out of one Bible we can derive many theologies even in conflict - all due to very different approaches and methods in translation. Yet, even in a bad translation, such as the Bishop’s Bible of 1568, all of the core doctrines and messages are there. So, while the knowledge of linguistics might be better today than in the past, that does not necessarily mean we have more accurate translations, because not all translation committees or publishers are dedicated to being honest with the text or respectful with the history of Christendom. Finally, for those who understand languages and history, and are amused by pious frauds and fictions, consider the King James Version, which is argued to rest on the Hebrew while rejecting the Latin, yet which uses the Latin word Lucifer rather than the Hebrew word Helel in the aformentioned passage in Isaiah. (The King James Version is also unique in translations in that the word Ethiopia, a place name, rather than Cush, a person, appears in Genesis chapter 2; and the word Easter appear in Acts chapter 12, though the Greek and Latin are clear that Passover is the correct and accurate word).

Q: Aren't there translation issues with the Latin Vulgate and the Douai Reims translation?

The Latin Vulgate translation produced by Jerome has been the Bible in use by Christians practicing the Latin Roman Catholic rite for over 1,500 years. That translation was upheld as the official translation for use in church services by the Council of Trent. That said, the Latin Vulgate and its English translation that comes to us as the Douai Reims Version suggest that a hybrid theory in translation was used. On one hand, literalness was employed as a whole in translation. In many instances, Jerome and the English language translators relied on the Greek Septuagint rather than the Hebrew as was the case in Genesis chapter 6 when the Greek word Gigantes resulted int the word Giants, rather than the Hebrew word Nephilim to convey the more accurate sense of Fallen Ones, who indeed were giants that had inhabited the earth before the flood. In other places, Jerome and the English language translators appear to have imposed a doctrinal position onto the translation of the text rather than translate word for word. For example, as noted earlier the passage in Isaiah 17 where the word Lucifer appears suggests that a theology, or a secondary meaning of the passage, may have been used. Similarly, the Our Father prayer in Matthew chapter 6 uses the words super substantial bread rather than daily bread, suggestive of the role of church doctrine in forcing theology onto the translation. At issue is the Greek word epiousios, which is also translated as daily in Luke chapter 11. (See Wikipedia article). We need to remember that a translation is just that: a translation. Any translation by its very nature is not the original Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek. When a translator does not touch a Hebrew word like Nephilim - fallen ones - and leaves that word in its Hebrew form, this should suggest a lack of the translator's mastery or courage in tackling a difficult or potentially controversial subject, and for the reader - even without a foot note - an indication that consulting a language or Bible dictionary would be appropriate for clarification.

With these aforementioned points made, the Douai Reims Version has the unique distinction of being the closest translation into the English language from the Latin Vulgate. The Latin Vulgate was the Bible in the West for well over a 1,000 years. The translators of the Latin Vulgate had fled England during a period of persecution during the English reformation. These English Catholics settled across the English Channel in the university cities of Douai and Rheims in France. There, they produced the most literal and direct translation of the medieval Latin into English with the New Testament appearing in 1582 and the Old Testament appearing in 1609 and 1610. Bishop Richard Challoner then modernized the spelling and verse divisions of the Douai Reims Version between 1763 and 1764. As such, there is no other translation that preserves the sense of the Latin that was familiar with Latin speaking Christians in Western Europe.

COSTS

Q: Why are your Bibles priced higher than other Bibles?

Our large format Bibles are intended for institutions like churches and collectors. A small group can easily raise the amount needed to own a Reproduction Bible for their own use. We develop our Reproduction Bibles from the ground up. That starts with digital type setting from scratch. That’s the easy part. The time period that we replicate dictates the font and the type of display letters. Those details are done by hand, and details take time. Once completed, we take our work through numerous test prints, which invariably requires fine tuning our work. We use archival quality papers that are heavy stock to replicate the period we seek to reproduce. Once completed, our large format* Bibles might then be printed on $2 million machines. There are only 200 digital printers in the world capable of printing our large format Reproduction Bibles. What is exciting about new technology is the ability of the printer to run folios through for a second pass to receive varnish over the text, which is what we will do to replicate the look of the text on the pages of our 42 line Gutenberg Bible in English thanks to one of the greatest pioneer in German engineering - Johannes Gutenberg. Our gold illuminated Bibles are painstakingly produced by hand by experienced and skilled artists. There are no short cuts. After the illumination is completed, the gatherings are sewn, and a period leather binding finishes our work. So, we are bringing together the best of old world and new world techniques in order to revive the best from the past in order to serve present and future generations. Best of all, our Reproduction Bibles are handcrafted in the United States of America.

Consider the alternative. A scroll on parchment of the Hebrew Bible - Genesis through Malachai - takes one year to produce by hand in Hebrew and runs approximately $40,000.

* Large format here is defined as a page size larger than 8 1/2" x 11". The large format 42 line Gutenberg Bible has page sizes of approximately 11" x 17". A Bible with a 13" x 19" page size would need to be printed on a $2 million machine. We have in house capability of printing 8 1/2" x 11" and 11" x 17" page sized Bibles.

EMPLOYMENT

Q: Are you hiring?

We always welcome inquiries. We have several other projects in mind to support our mission, and can only complete them with the right people, the right skills, and the right willingness and determination. If you have a particular skill set or subject matter expertise, which you think may lend itself to what we do, please feel free to contact us.

PARTNERING

Q: Have you considered “Crowd Funding?”

We were told that our projects would be ideal for crowd funding. Our initial thoughts were that we were not interested in hand outs. We would rather raise funds through our museum quality examples of our work to underwrite our projects. But, we know there are individuals as well as institutions who understand our vision, which goes beyond this immediate generation. Yes, we welcome partnering with like minded supporters.

We did not set up as an educational or religious non profit, because we did not want to allocate 30 to 40 percent of funds raised from foundations for the payroll of the fundraiser, who would take away from our research and creativity. Like it or not ... that is how that works. Because, we are not a non profit, contributions are not tax deductible.

Our vision of “crowd funding” is through patrons, like you, who support our vision by purchasing an illuminated poster from one of our Reproduction Bibles either for yourself or as a gift.